Four years ago this week, there was only one subject on Canadians’ minds: the incipient COVID-19 pandemic. Schools and businesses were locked down in most of the country. The death count was appalling: close to 1,900 in the first full week of the month. In all, about 4,300 Canadians would die that May – with far more brutal waves of infection and death to come.

The story is much different today. Thanks to the rapid development, approval and delivery of vaccines – an amazing human accomplishment that isn’t celebrated enough – COVID-19 has been brought to heel and is now largely seen as just one more viral disease, like the flu or common cold. The availability of home testing kits means most people who become infected by the latest variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus can manage the disease at home, and never trouble the health care system.

That’s good, but it hides the troubling fact that it is difficult to discern coherent policies at any level of government for continuing the fight against COVID-19, for dealing with its long-term effects, or for preparing for another pandemic.

First and foremost, the pandemic is still going on. While infection rates are stable, there were still 3,320 new cases and 94 deaths from April 7 to April 20, according to federal data. That’s more than six deaths a day. And the number of cases is undercounted, given that many people won’t bother to report a positive home test to the government.

As well, there is a continuing “long COVID” crisis in Canada, in which symptoms – sometimes debilitating ones – last months or even years. A Statistics Canada report from last December found that 2.1 million people were experiencing long COVID symptoms as of June, 2023.

Meanwhile, vaccination rates have plunged. Barely one in five people had received the recommended dose for their age group and health status as of the end of February, according to federal data. Even the rates for the vulnerable elderly have fallen. Only 55 per cent of people aged 70-79, and 61 per cent of those over 80, have had the recommended dose.

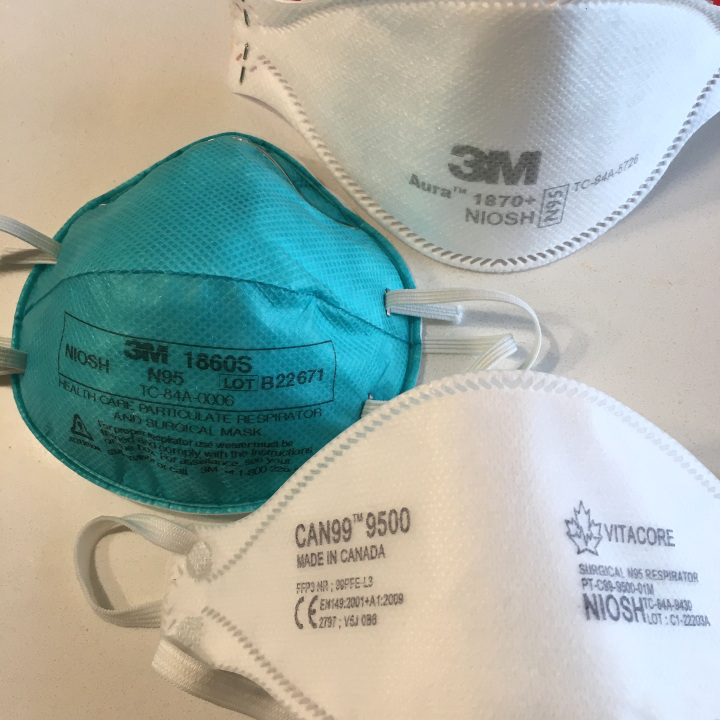

Equally concerning is that there has never been a public inquiry into the handling of the crisis. That means the public can have little confidence that, in a future epidemic or pandemic, there won’t be a repeat of Ontario’s infamous snafu, where the provincial government put millions of dollars of personal protection equipment into a warehouse after the 2003 SARS epidemic in Toronto, and then let the contents expire without being replaced, contributing to a shortage of PPE in the COVID crisis.

Ottawa has signed a 10-year agreement with a Montreal company to supply N95 respirators and surgical masks, but that hardly counts as a comprehensive plan to build a national stockpile of PPE available to every province.

On the vaccine-supply front, Moderna, one of the developers of the mRNA COVID vaccine, is opening a plant in Montreal this year that will provide Ottawa with a minimum of 30 million doses a year. The facility will also research emerging viruses and develop new vaccines.

But that bit of good news can’t hide the fact that there is no joint federal-provincial planning for handling the next pandemic. It’s more accurate to say the provinces and Ottawa are operating in their own silos, making little apparent effort to co-operate on a national scale and instead looking after partisan political concerns.