Remember when we thought Covid was a two-week illness? So does Michael Peluso, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

He recalls the rush to study acute Covid infection, and the crush of resulting papers. But Peluso, an HIV researcher, knew what his team excelled at: following people over the long term.

So they adapted their HIV research infrastructure to study Covid patients. The LIINC program, short for “Long-term Impact of Infection with Novel Coronavirus,” started in San Francisco at the very beginning of the pandemic. By April 2020, the team was already seeing patients come in with lingering illness and effects of Covid — in those early days still unnamed and unpublicized as long Covid. They planned to follow people’s progress for three months after they were infected with the virus.

By the fall, the investigators had rewritten their plans. Some people’s symptoms were so persistent, Peluso realized they had to follow patients for longer. Research published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine builds on years of that data. In some cases, the team followed patients up to 900 days, making it one of the longest studies of long Covid (most studies launched in 2021 or 2022, including the NIH-funded RECOVER program).

Investigators found long-lasting immune activation months and even years after infection. And, even more concerning, they report what looked like lingering SARS-CoV-2 virus in participants’ guts. Even those who’d had Covid but no continuing symptoms had different results than those who’d never been infected.

The team’s big idea — hypothesizing in early 2020 that, contrary to the popular narrative, Covid would last in the body — was “visionary,” long Covid researcher Ziyad Al-Aly said. “A lot of people don’t think like that.” Al-Aly was not involved with the study, but has published other long-term studies of Covid patients. He is chief of research and development at the VA Saint Louis Healthcare System.

The research makes use of novel technology developed by the paper’s senior authors, Henry Vanbrocklin, professor in the department of radiology at UCSF, and associate professor of medicine Timothy Henrich. They figured out in the last several years they could use an antibody that bound to HIV’s code protein as a guide to see viral reservoirs. The HIV antibody, labeled with radioactive isotopes, could be tracked with imaging as it moved through the body and migrated to infected tissues.

There were no antibodies to latch onto early in the coronavirus pandemic. Vanbrocklin instead used a chemical agent, called F-AraG, that binds to activated T cells — immune cells that flood into infected tissues. They injected F-AraG into patients, and into a scan they went.

Tissues full of activated T cells glowed in the resulting image. Researchers found more glowing sites of immune activation in people who had been infected with Covid than in those who had not, including: the brain stem, spinal cord, cardiopulmonary tissues, bone marrow, upper pharynx, chest lymph nodes, and gut wall.

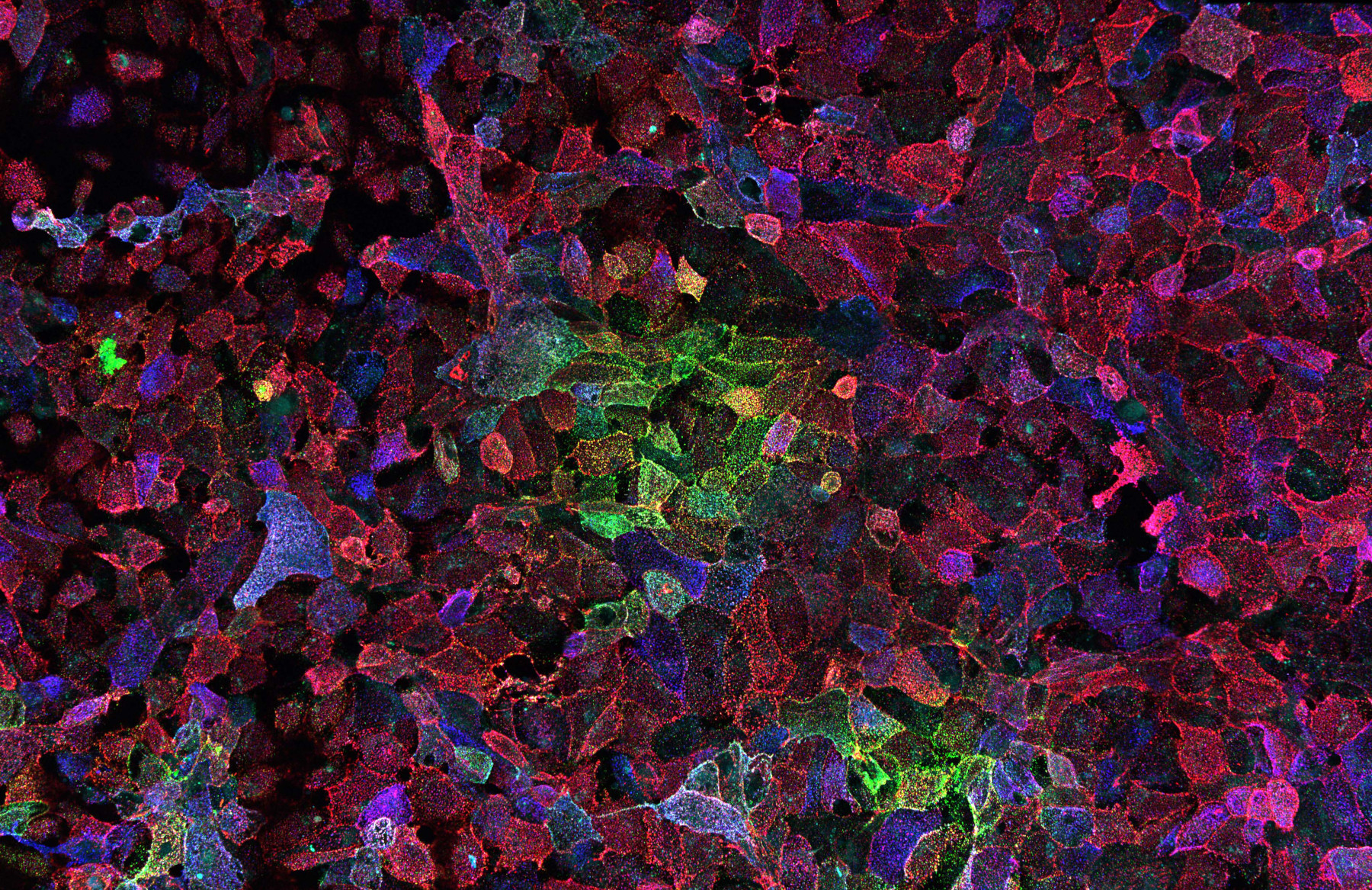

Image description: Photo of cells infected with SARS-CoV-2. The reds and greens in the image represent cells infected with the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Photo: Alberto Domingo Lopez-Munoz, Laboratory of Viral Diseases, NIAID/NIH.